NAD+ (100mg & 500mg)

Price range: $46.00 through $179.00

NAD+ peptides are Synthesized and Lyophilized in the USA.

Discount per Quantity

| Quantity | 5 - 9 | 10 + |

|---|---|---|

| Discount | 5% | 10% |

| Price | Price range: $43.70 through $170.05 | Price range: $41.40 through $161.10 |

FREE - USPS priority shipping

Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (NAD+) Peptide

Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (NAD+) is an oxidized form of NADH (Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Hydroxide). NAD+ is a component of the Electron Transport Chain (ETC), which researchers have suggested to act in carrying electrons and thus energy within cells. The peptide has also been posited to potentially act as a mediator for various physiological processes, such as post-translational modification of the proteins and activation/deactivation of some enzymes. It is believed to be a critical component in maintaining cell-to-cell communication.

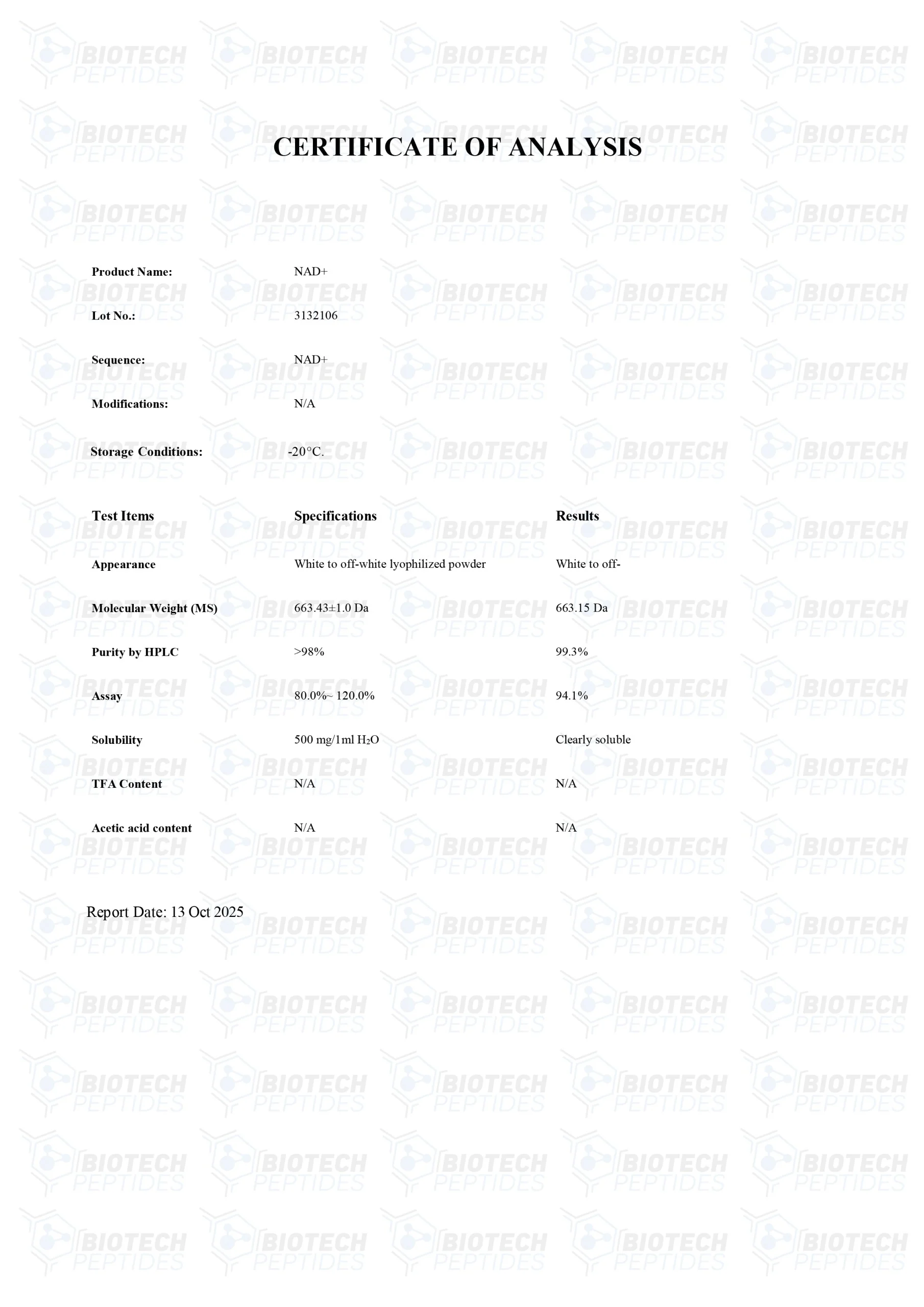

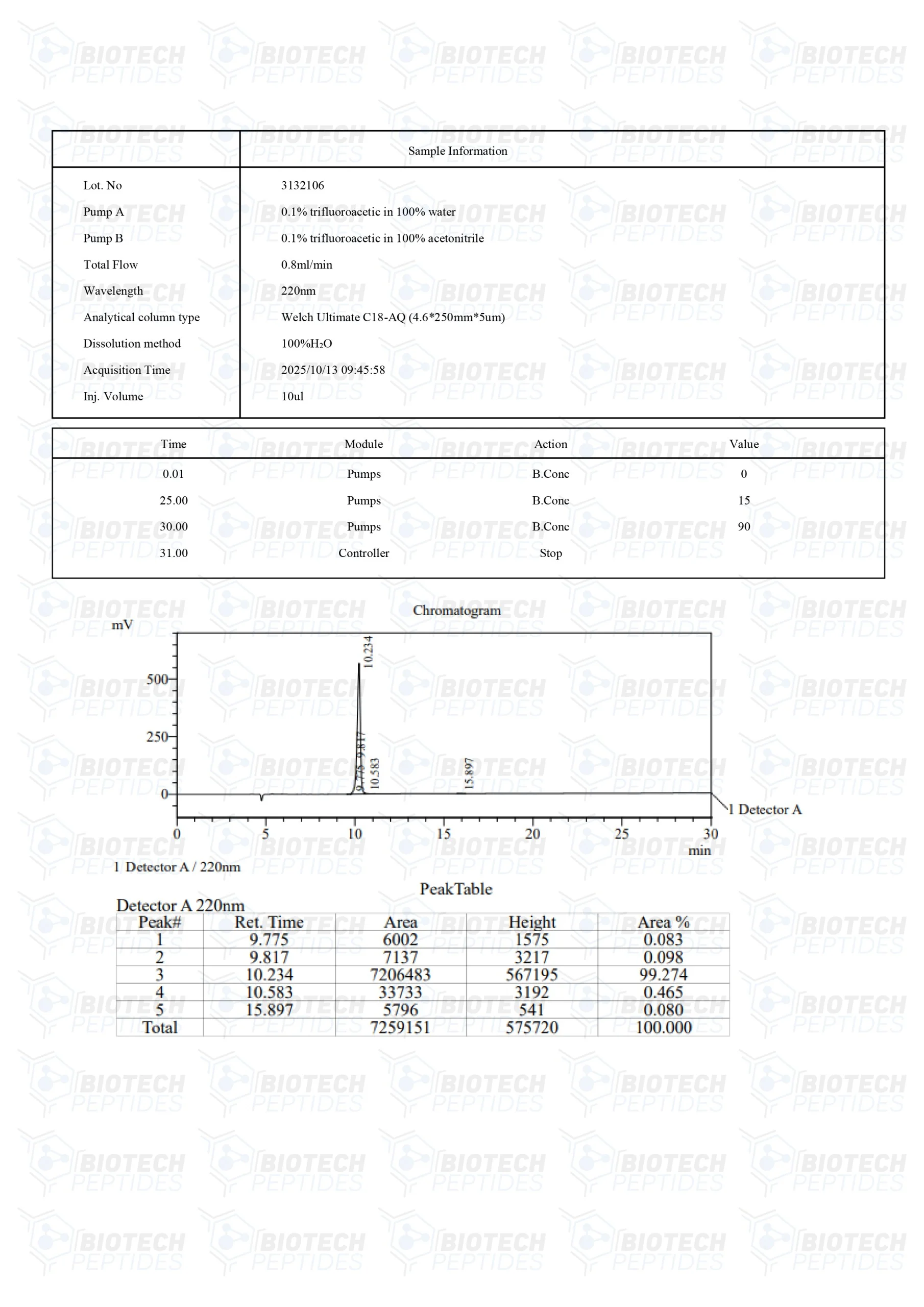

Specifications

MOLECULAR WEIGHT: 663.43 g/mol

MOLECULAR FORMULA: C21H27N7O14P2

SYNONYMS: Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide, Beta-NAD, NAD, Endopride

NAD+ Research

NAD+ and Cellular Aging

Mitochondria serve as a platform for primary metabolic functions such as intracellular signaling and regulation of innate immunity. These processes appear directly impacted by mitochondrial senescence and ultimately alter cellular metabolism, inflammation, and even stem cell activity.[1] These altogether may reduce the pace of tissue repair following damage. This illustrates the extent to which mitochondria are involved in cellular age-related decline in tissue and organ function. Researchers consider that in the course of manipulating mitochondrial activity, they may potentially slow, cease, or even reverse the process of cellular aging.

A deficiency of NAD+ in the cell appears to induce a pseudo-hypoxic state, which interrupts signaling within the nucleus.[2] The scientists suggest that “raising NAD+ levels in old mice restores mitochondrial function to that of a young mouse in a SIRT1-dependent manner.” The mechanism underlying this property appears to involve the activation of the SIRT 1 function, whereby a gene encodes an enzyme called Sirtuin-1 (NAD+ dependent Deacetylase Sirtuin-1). Sirtuin-1 then may regulate the mediators involved in metabolism, inflammation, and the longevity of cells.[3]

Sirtuins-1 is a member of a class of proteins called sirtuins, which are posited to require NAD+ as a cofactor to carry out possible enzymatic activities. They are potentially involved in various cellular processes, including DNA repair, gene expression, and metabolic regulation. They have been linked to cellular longevity and lifespan.[4]

NAD+ and Muscle Cell Function

The endogenous decline in muscle cell function is associated with mitochondrial senescence. Scientists consider that the decline occurs in two steps. The first, to some extent reversible, involves declined expression of mitochondrial genes. These genes appear to be responsible for oxidative phosphorylation (the process by which mitochondria produce energy). The second, irreversible, consists of a decline in genes responsible for oxidative phosphorylation in the nucleus.

Experiments using murine models have reported an apparent step 1 reversal with the exposure of additional NAD+ before the cell progresses to step 2.[5] The mechanism behind this intervention in mitochondrial aging may involve stabilizing the activity of Peroxisome Proliferator-activated Receptor Gamma Co-activator 1-alpha (PGC-1-alpha). Studies have suggested that the action mentioned above produced in the mitochondria may be similar to exercise on the mitochondria of skeletal muscles.[6]

NAD+ and Neurodegeneration

NAD+ is a cofactor that may exert a possible neuroprotective action.[7] It has been posited that this can be done by supporting mitochondrial function and reducing the production of reactive oxidative stress (ROS). ROS is responsible for inflammatory changes associated with injury and degenerative changes associated with cellular aging. This association provides the basis for certain neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s, and Parkinson’s.

Research conducted on mice suggested the potential for NAD+ to protect against progressive motor deficits and the death of dopamine-producing cells in the substantia nigra.[8] According to the researchers, “These results add credence to the beneficial role of NAD against parkinsonian neurodegeneration in mouse models of PD, provide evidence for the potential of NAD for the prevention of PD, and suggest that NAD prevents pathological changes in PD via decreasing mitochondrial dysfunctions.” The research findings implied that although NAD+ doesn’t appear to alleviate the symptoms, it may slow the progress of if not entirely mitigate, the development of Parkinson’s disease.

NAD+ and Inflammation

NAMPT is an enzyme that is associated with inflammation. It appears over-expressed in certain types of cancer cells. An increase in the levels of NAMPT appears to correlate to NAD+ levels and vice versa.[9] The NAMPT-associated inflammation appears to occur in cancer cells, and research models of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. NAMPT may be a potent activator of inflammation, while cellular inflammation levels may decrease dramatically following the introduction of NAD+. The alteration of NAD+ levels might influence inflammatory pathways within cells, suggesting a possible approach to modulate inflammatory responses at the cellular level.

NAD+ and DNA Integrity

Research has investigated how NAD+ might protect DNA integrity through its association with enzymes called poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs).[10] NAD+ is thought to serve as a substrate for PARP enzymes, which may participate in DNA repair mechanisms by attaching ADP-ribose (ADPr) units to specific proteins. The enzyme PARP-1, the first discovered member of the PARP family, is believed to become active during DNA damage by adding chains of poly(ADP-ribose) (pADPr) to proteins.

These pADPr chains might function as scaffolds, potentially attracting DNA repair proteins to the sites of damage and possibly assisting in loosening the chromatin structure to facilitate repair processes. The study also proposes that pADPr may have additional roles within the cell nucleus under normal conditions, such as influencing gene transcription, altering chromatin architecture, and maintaining telomeres—the protective ends of chromosomes. These functions are presumably mediated by PARP enzymes using NAD+ to create ADPr modifications on proteins. Different PARP enzymes may work together, with some initiating the addition of single ADP-ribose units (a process referred to as mono(ADP-ribosyl)ation) and others extending these into longer pADPr chains. This sequential modification might support the specificity and efficiency of DNA repair mechanisms.

This type of research highlights that other enzymes consuming NAD+, such as sirtuins, might also contribute to maintaining DNA integrity. Sirtuins, exemplified by the yeast protein Sir2p, are associated with gene silencing, chromosome stability, and cellular aging processes. Specifically, the sirtuin referred to as SIRT6 is reported to add a single ADP-ribose unit to PARP-1 in response to DNA damage, which may then encourage further addition of poly(ADP-ribose) chains to PARP-1. This suggests there might be an interaction between NAD+-dependent signaling pathways in preserving genomic stability.

NAD+ and Cell Survival

As a crucial coenzyme that plays a significant role in cellular energy metabolism, NAD+ may participate in various signaling pathways influencing cell survival. Researchers suggest that under conditions of oxidative stress, oxidative DNA damage may accumulate.[11] This accumulation might result from increased attacks by reactive oxygen species (ROS) on DNA and a potential decline in the cell's DNA repair capabilities. The buildup of DNA lesions may activate PARP-1, leading to NAD+ depletion and possibly resulting in cell death.

In experiments using neuronal cell cultures subjected to oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD)—a laboratory model that simulates ischemic injury by reducing oxygen and glucose availability—it was observed that directly adding NAD+ either before or after OGD seemed to reduce cell death and decrease DNA damage.[11] This protective action appeared to depend on the concentration of NAD+ and the timing of its administration. It is hypothesized that supplementing NAD+ might restore nuclear DNA repair activities by mitigating the phosphorylation (addition of phosphate groups) of serine amino acids on essential enzymes involved in base-excision repair (BER), such as apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 (APE1) and DNA polymerase beta (βpol). Reactivating these DNA repair mechanisms might be a key factor mediating the neuroprotective actions of NAD+. Further observations suggest that replenishing NAD+ may mitigate the typical decline in BER activities that occurs after OGD.

The loss of BER function in neurons exposed to OGD is thought to be due to phosphorylation on serine and threonine residues of the rate-limiting enzymes APE1 and βpol. NAD+ might help reinstate the activities of these enzymes by potentially inhibiting protein kinases (enzymes that add phosphate groups) or activating phosphatases (enzymes that remove phosphate groups) that regulate their phosphorylation states. Experiments involving the reduction (knockdown) of APE1 expression indicated that this significantly lessened the prosurvival relevance of NAD+ supplementation, implying that the functional integrity of the BER pathway may be crucial for the observed neuroprotection. However, since the knockdown of APE1 did not eliminate the prosurvival action, it is possible that NAD+ also activates additional survival mechanisms. These mechanisms might include supporting the delivery of substrates to mitochondria under conditions where NAD+ is being consumed, thereby promoting energy production, or activating NAD+-dependent processes such as SIRT deacetylase activities. Sirtuins may influence cell survival through chromatin remodeling and the suppression of proteins involved in apoptosis (programmed cell death).

Disclaimer: The products mentioned are not intended for human or animal consumption. Research chemicals are intended solely for laboratory experimentation and/or in-vitro testing. Bodily introduction of any sort is strictly prohibited by law. All purchases are limited to licensed researchers and/or qualified professionals. All information shared in this article is for educational purposes only.

References

- Sun N, Youle RJ, Finkel T. The Mitochondrial Basis of Aging. Mol Cell. 2016 Mar 3;61(5):654-666. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.01.028. PMID: 26942670; PMCID: PMC4779179.

- Gomes AP, Price NL, Ling AJ, Moslehi JJ, Montgomery MK, Rajman L, White JP, Teodoro JS, Wrann CD, Hubbard BP, Mercken EM, Palmeira CM, de Cabo R, Rolo AP, Turner N, Bell EL, Sinclair DA. Declining NAD(+) induces a pseudohypoxic state disrupting nuclear-mitochondrial communication during aging. Cell. 2013 Dec 19;155(7):1624-38. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.037. PMID: 24360282; PMCID: PMC4076149.

- Imai S, Guarente L. NAD+ and sirtuins in aging and disease. Trends Cell Biol. 2014 Aug;24(8):464-71. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.04.002. Epub 2014 Apr 29. PMID: 24786309; PMCID: PMC4112140.

- Wątroba, M., Dudek, I., Skoda, M., Stangret, A., Rzodkiewicz, P., & Szukiewicz, D. (2017). Sirtuins, epigenetics and longevity. Ageing research reviews, 40, 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2017.08.001

- Mendelsohn AR, Larrick JW. Partial reversal of skeletal muscle aging by restoration of normal NAD⁺ levels. Rejuvenation Res. 2014 Feb;17(1):62-9. doi: 10.1089/rej.2014.1546. PMID: 24410488.

- Kang C, Chung E, Diffee G, Ji LL. Exercise training attenuates aging-associated mitochondrial dysfunction in rat skeletal muscle: role of PGC-1α. Exp Gerontol. 2013 Nov;48(11):1343-50. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2013.08.004. Epub 2013 Aug 30. PMID: 23994518.

- Matthews RT, Yang L, Browne S, Baik M, Beal MF. Coenzyme Q10 administration increases brain mitochondrial concentrations and exerts neuroprotective effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998 Jul 21;95(15):8892-7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8892. PMID: 9671775; PMCID: PMC21173.

- Shan C, Gong YL, Zhuang QQ, Hou YF, Wang SM, Zhu Q, Huang GR, Tao B, Sun LH, Zhao HY, Li ST, Liu JM. Protective effects of β- nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide against motor deficits and dopaminergic neuronal damage in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019 Aug 30;94:109670. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2019.109670. Epub 2019 Jun 17. PMID: 31220519.

- Garten A, Schuster S, Penke M, Gorski T, de Giorgis T, Kiess W. Physiological and pathophysiological roles of NAMPT and NAD metabolism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015 Sep;11(9):535-46. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.117. Epub 2015 Jul 28. PMID: 26215259.

- Leung A, Todorova T, Ando Y, Chang P. Poly(ADP-ribose) regulates post-transcriptional gene regulation in the cytoplasm. RNA Biol. 2012 May;9(5):542-8. doi: 10.4161/rna.19899. Epub 2012 May 1. PMID: 22531498; PMCID: PMC3495734.

- Wang S, Xing Z, Vosler PS, Yin H, Li W, Zhang F, Signore AP, Stetler RA, Gao Y, Chen J. Cellular NAD replenishment confers marked neuroprotection against ischemic cell death: role of enhanced DNA repair. Stroke. 2008 Sep;39(9):2587-95. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.509158. Epub 2008 Jul 10. PMID: 18617666; PMCID: PMC2743302.