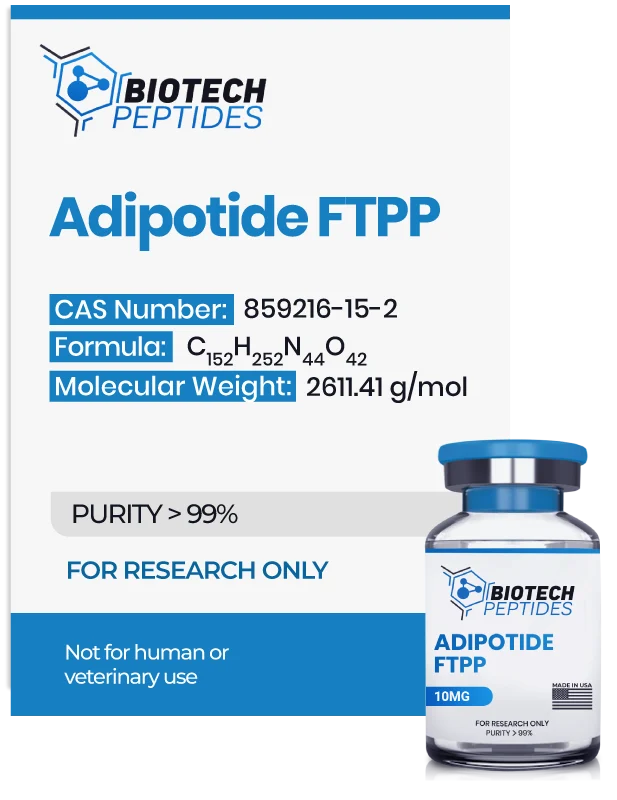

Adipotide FTPP (10mg)

$77.00

Adipotide FTPP peptides are Synthesized and Lyophilized in the USA.

Discount per Quantity

| Quantity | 5 - 9 | 10 + |

|---|---|---|

| Discount | 5% | 10% |

| Price | $73.15 | $69.30 |

FREE - USPS priority shipping

Adipotide FTPP Peptide

Adipotide FTPP is a category of proapoptotic peptides intended to eliminate fat cells.[1] They appear to cut off the blood supply specifically to the adipose tissues and not the vessels supplying blood to the rest of the organism. Reports of studies performed in monkeys have suggested their potential to induce weight loss, which may improve symptoms of insulin resistance and reduces the symptoms of type 2 diabetes.

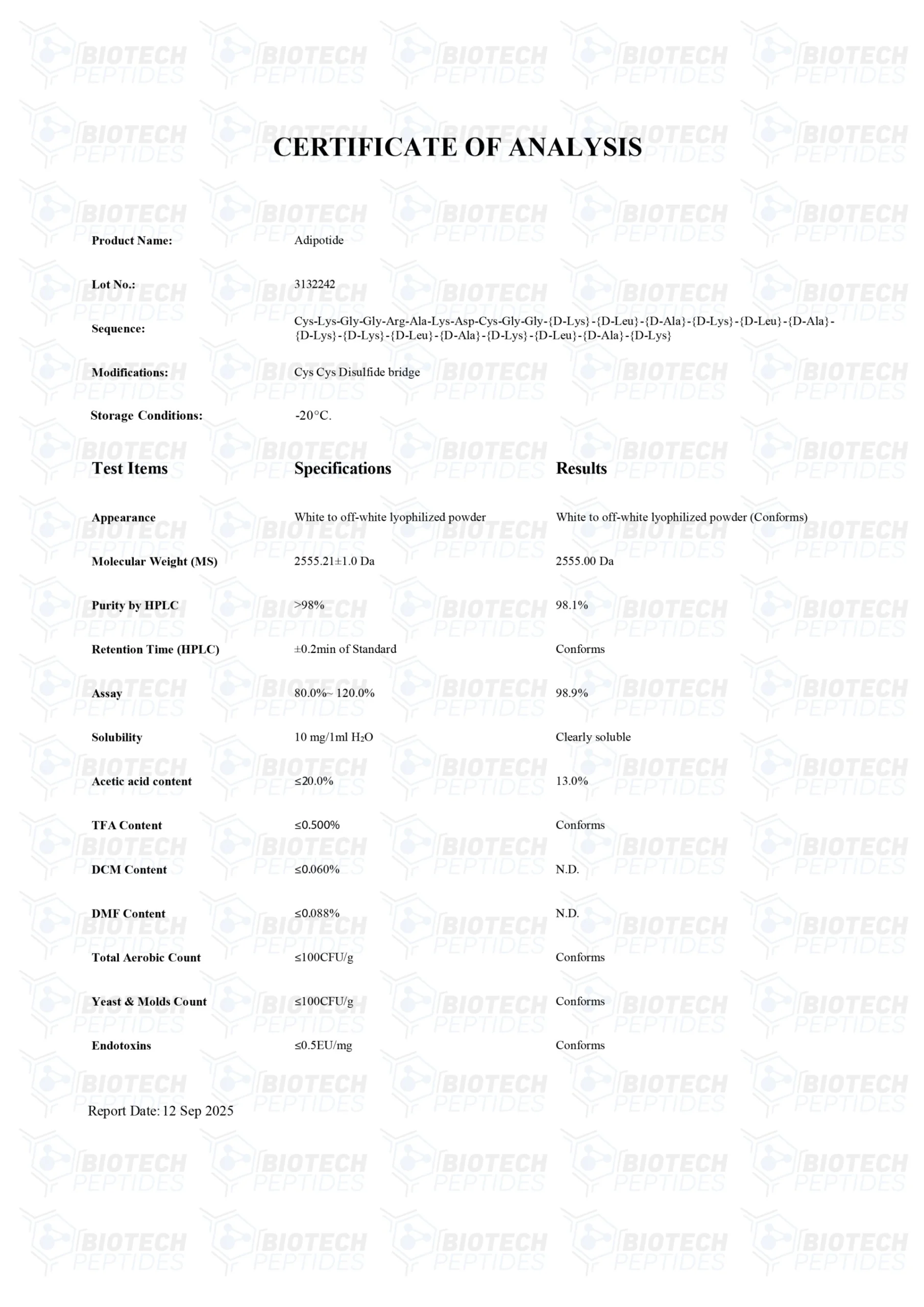

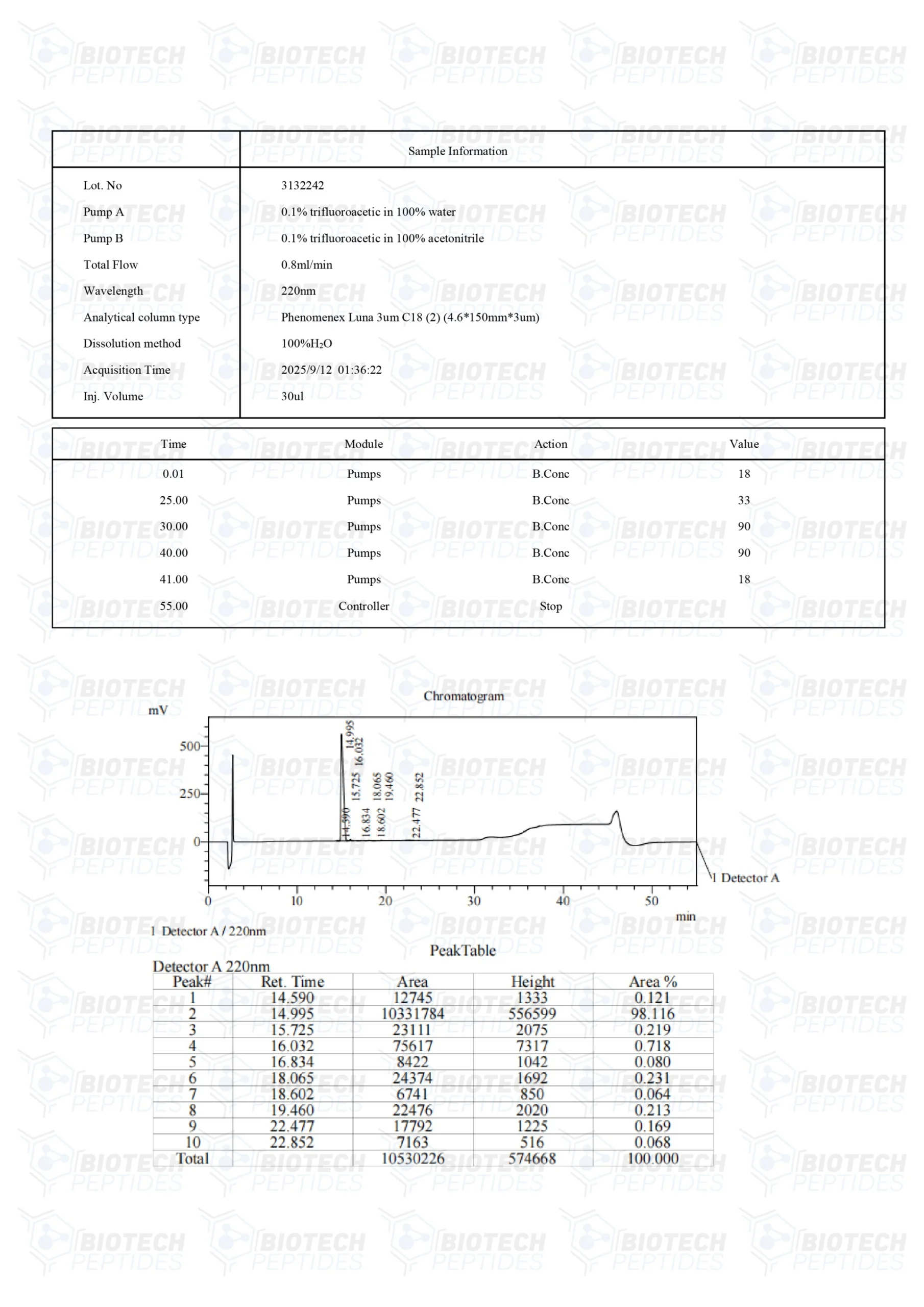

Specifications

Other Known Titles: Adipotide

Molecular Formula: C152H252N44O42

Molecular Weight: 2611.41 g/mol

Sequence: Cys-Lys-Gly-Gly-Arg-Ala-Lys-Asp-Cys—Gly-Gly--(Lys-Leu-Ala-Lys-Leu-Ala-Lys)2

Adipotide FTPP Research

Adipotide FTPP Mechanism of Action

Adipotide has been suggested to exert action by binding to the receptors for two specific proteins, ANXA2 (Annexin A2) and prohibitin (PHB). It appears that these receptors may be expressed in a wide range of cells, but immunohistochemical analysis hypothesizes that they potentially form a unique ANXA2-prohibitin receptor system that are apparently found in white fat tissue.[2] It appears that these receptors were found on the endothelial cells of blood vessels that support white fat cells. Furthermore, research suggests that these receptors may play a role in regulating fatty acid transport in white adipose tissues (WAT).[3] To potentially explore this notion, the researchers disrupted the binding between ANXA2 and prohibitin genetically or by utilizing a blocking peptide. Their findings seem to indicate that the efficiency of fatty acid transport might depend on the interaction between ANXA2 and prohibitin. Moreover, the study suggests that the interaction between ANXA2 and prohibitin may facilitate the transport of fatty acids from the endothelium into adipocytes. The researchers also stumbled upon the revelation that ANXA2 and prohibitin form a complex alongside the fatty acid transporter CD36.

This intricate connection involving ANXA2, prohibitin, and CD36 potentially plays a role in mediating fatty acid transport in white adipose tissues. Furthermore, the researchers noticed that the coexistence of prohibitin and CD36 on the surface of adipocytes appears to be induced by extracellular fatty acids. This lead them to the hypothesis that the presence of fatty acids in the external environment may trigger the interaction between prohibitin and CD36 on the adipocyte surface. Hypothetically, inhibiting the ANXA2 protein may lead to hypertrophy of white adipose cells due to reduced uptake of fatty acids. On the other hand, prohibitin is a multifunctional membrane-associated protein that may be thought to regulate cell survival and growth. By shuttling from the cell's membrane to its nucleus, it may hypothetically trigger apoptosis. Thus, the scientists commented that “suggest that an unrecognized biochemical interaction between ANX2 and PHB regulates CD36-mediated fatty acid transport in WAT, thus revealing a new potential pathway for intervention in metabolic diseases.”

Adipotide FTPP Structure

Adipotide appears to have a unique structure consisting of the amino acid sequence GKGGRAKDC-GG-D(KLAKLAK)2. The nine amino acid sequence CKGGRAKDC may exhibit a specific affinity to the ANXA2-prohibitin receptor system found in the blood vessels supporting white adipose cells.[4] The researchers utilized phage display, a technique that is considered to enable the identification of specific peptide motifs, to isolate a peptide sequence CKGGRAKDC. Moreover, the CKGGRAKDC peptide appears to associate with a membrane protein called prohibitin, which has been identified as a potential vascular marker of adipose tissue. By directing a proapoptotic peptide towards prohibitin in the adipose vasculature, the researchers induced the ablation (removal) of white fat. This resulted in the possible resorption of established white adipose tissue and the potential normalization of metabolism. As a consequence, rapid obesity reversal was reported to be achieved. It is suggested that prohibitin is expressed in the blood vessels of white fat. However, it is crucial to note that the study solely focuses on elucidating the mechanisms involved and did not provide any definitive suggestions or implications regarding its potential.

At the same time, (KLAKLAK)2 may disrupt mitochondrial membranes upon receptor-mediated cell internalization and possibly cause programmed cell death. As Adipotide may bind to prohibitin in white adipose vasculature, it potentially triggers apoptosis and hypothetically results in the ablation of white fat cells. According to research, Adipotide and other similar peptidomimetics may hold potential for reducing both subcutaneous and visceral fat and may even target intra-organ fat, such as in fatty liver.[5] In fact, the researchers posit that “vascular-targeted nanotherapy has the potential to contribute to the control of adipose function and ectopic fat deposition associated with obesity and the metabolic syndrome.”

Adipotide FTPP and Cancer Cells

Cancerous tissues can grow rapidly and become metastatic due to the large network of blood vessels. Suppose prohibitin, found in several cancer types, is targeted. In that case, it may be possible to mitigate cancer in a more focused manner and avoid the associated negative impacts brought about due to damage to surrounding tissues in certain chemotherapy scenarios. Some researchers posit that there may be a potential association between excess fat tissue cells and the occurrence of cancer cells. One study discussed several potential mechanisms that may help explain the potential association between obesity and the occurrence of aggressive prostate cancer cells (PCa), aka tumorigenesis.[6] Three main mechanisms are highlighted: the insulin/insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1 axis, sex hormones, and adipokine signaling. The insulin/IGF-1 axis appears implicated in the potential tumorigenesis associated with obesity, including PCa. It is suggested that high insulin levels resulting from a hyperinsulinemic state induced by diet may potentially accelerate tumor cell growth in PCa models.

The presence of the insulin receptor in PCa indicates a potential for insulin to stimulate its growth. Studies have associated higher serum C-peptide concentrations, serving as a surrogate for insulin levels, with an increase in PCa-specific mortality. Thus, it is hypothesized that insulin likely plays a key role in potentially explaining the connection between obesity and aggressive PCa. Obesity and hyperinsulinemia also potentially result in increased levels of bioactive IGF-1, a growth factor implicated in various cancers. Elevated circulating IGF-1 has been associated with an increased incidence of PCa, particularly in detectable cases. The upregulation of the IGF-1 receptor accompanies the transition of androgen-dependent PCa cell lines to androgen independence, and studies have suggested that IGF-1 potentially promotes PCa progression. Therefore, it is posited that IGF-1 may be associated with aggressive PCa, although its association with less aggressive, PSA-detected tumors remains uncertain. Testosterone (T) is potentially aromatized to estradiol (E) within adipocytes and prostate cells.

Obesity, characterized by increased adipose tissue mass and upregulation of the aromatization pathway, leads to potentially elevated serum and intracellular E levels. Although epidemiologic data does not consistently support a clear association between serum E and PCa risk, preclinical studies suggest that E may potentially promote PCa development and progression. Obesity is considered a state of chronic subclinical inflammation influenced by altered levels of adipokines. Leptin, potentially elevated in obesity, appears to exert pro-tumor impacts in PCa cell lines, inducing proliferation, inhibiting apoptosis, and increasing migration. However, epidemiologic studies do not consistently report a clear positive association between leptin and PCa risk or fatal PCa. On the other hand, adiponectin, which is considered to be reduced in obesity, predominantly exhibits anti-tumor effects. Reduced levels of adiponectin have potentially been associated with metastatic and fatal PCa. While the role of leptin in the link between obesity and aggressive PCa remains unclear, adiponectin appears to be associated with advanced aggressive PCa, reflecting the overall connection between obesity and PCa.

Obesity is also potentially associated with elevated serum interleukin (IL)-6 levels, primarily originating from adipose tissue. PCa cells and primary PCas potentially produce IL-6 and express IL-6 receptors, enabling them to respond to this proinflammatory adipokine.

Adipotide and Glucose Tolerance

Glucose tolerance, a common parameter in characterizing diabetes, is studied by performing a blood test and confirmed by testing fasting glucose levels. In another method, a specific amount of glucose is consumed, and then blood sugar levels are estimated. Metabolic syndromes such as diabetes have traditionally been controlled by nutritional intake and physical activity. Both require immense patience and dedication as the outcomes can take months, if not years, to exhibit significant improvement. Research with Adipotides has noted rapid weight-independent improvement in glucose tolerance in animal research models.[7] This highlights the observation that reducing white fat by adipotide FTPP may simultaneously reduce glucose tolerance irrespective of the model’s weight. Although it is unclear whether Adipotide FTPP peptide may directly induce fat loss or whether it may decrease the appetite (an indirect factor), the former is more likely as changes in fat cell density and improved glucose tolerance have been observed even without associated weight loss.

Adipotide And Fat Loss

Research on rhesus monkeys suggested the potential of this novel peptide to induce apoptosis, specifically in the vessels supplying blood to the white adipose tissues.[8] The result being no blood cells and hence, the ensuing death of these fat cells. The eventual outcomes reported were rapid weight loss, decreased body mass index, and improved insulin sensitivity. Such changes were attributed in part to the potential of Adipotide FTPP to change the eating pattern of the monkeys, as the monkeys who exhibit a positive weight loss also exhibited a reduced appetite. Research has suggested that Adipotide is associated with prohibitin, a membrane protein receptor present in blood vessels of white fat tissues and some cancer cells.

Future Research

Anti-angiogenic molecules like Adipotites target the blood vessels and are considered a potential agent in cancer studies.[9] Most of the research with Adipotides have been focused on their potential in fat loss and diabetes. They have been suggested to target the blood vessels of adipose tissues in which they supposedly induce apoptosis.

Disclaimer: The products mentioned are not intended for human or animal consumption. Research chemicals are intended solely for laboratory experimentation and/or in-vitro testing. Bodily introduction of any sort is strictly prohibited by law. All purchases are limited to licensed researchers and/or qualified professionals. All information shared in this article is for educational purposes only.

References

- Kolonin, M. G., Saha, P. K., Chan, L., Pasqualini, R., & Arap, W. (2004). Reversal of obesity by targeted ablation of adipose tissue. Nature medicine, 10(6), 625–632. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm1048

- Staquicini, F. I., Cardó-Vila, M., Kolonin, M. G., Trepel, M., Edwards, J. K., Nunes, D. N., Sergeeva, A., Efstathiou, E., Sun, J., Almeida, N. F., Tu, S. M., Botz, G. H., Wallace, M. J., O'Connell, D. J., Krajewski, S., Gershenwald, J. E., Molldrem, J. J., Flamm, A. L., Koivunen, E., Pentz, R. D., … Arap, W. (2011). Vascular ligand-receptor mapping by direct combinatorial selection in cancer patients. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108(46), 18637–18642. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1114503108

- Salameh, A., Daquinag, A. C., Staquicini, D. I., An, Z., Hajjar, K. A., Pasqualini, R., Arap, W., & Kolonin, M. G. (2016). Prohibitin/annexin 2 interaction regulates fatty acid transport in adipose tissue. JCI insight, 1(10), e86351. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.86351

- Kolonin, M. G., Saha, P. K., Chan, L., Pasqualini, R., & Arap, W. (2004). Reversal of obesity by targeted ablation of adipose tissue. Nature medicine, 10(6), 625–632. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm1048

- Hossen, N., Kajimoto, K., Akita, H., Hyodo, M., & Harashima, H. (2013). A comparative study between nanoparticle-targeted therapeutics and bioconjugates as obesity medication. Journal of controlled release : official journal of the Controlled Release Society, 171(2), 104–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.07.013

- Allott, E. H., Masko, E. M., & Freedland, S. J. (2013). Obesity and prostate cancer: weighing the evidence. European urology, 63(5), 800–809. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2012.11.013

- Hossen, N., Kajimoto, K., Akita, H., Hyodo, M., & Harashima, H. (2013). A comparative study between nanoparticle-targeted therapeutics and bioconjugates as obesity medication. Journal of controlled release : official journal of the Controlled Release Society, 171(2), 104–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.07.013

- Barnhart, K. F., Christianson, D. R., Hanley, P. W., Driessen, W. H., Bernacky, B. J., Baze, W. B., Wen, S., Tian, M., Ma, J., Kolonin, M. G., Saha, P. K., Do, K. A., Hulvat, J. F., Gelovani, J. G., Chan, L., Arap, W., & Pasqualini, R. (2011). A peptidomimetic targeting white fat causes weight loss and improved insulin resistance in obese monkeys. Science translational medicine, 3(108), 108ra112. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3002621

- Thuaud, F., Ribeiro, N., Nebigil, C. G., & Désaubry, L. (2013). Prohibitin ligands in cell death and survival: mode of action and therapeutic potential. Chemistry & biology, 20(3), 316–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.02.006